Future Horizons:

10-yearhorizon

Individual data-gathering creates new peacekeeping tools but raises serious issues of privacy and exclusion

25-yearhorizon

Climate change and conflict increases use of peace modelling

The field has been bolstered by a number of successes, particularly with the application of AI techniques.18 For example, machine-learning-based analysis of newspaper text can predict the onset of conflict, becoming particularly useful when risk in previously peaceful countries arises.19,20 Analysis of food prices shows that increases beyond a threshold level are correlated with civil unrest in many parts of the world.21 Granular, actor-based conflict data22,23 gives rise to models that take it into account.24,25 The ability to model migration patterns on a global scale using anonymised Facebook data is also a significant step.26

Research in the field sees policies for conflict prevention — mediation, development aid, institutional reform and building state capacity, for example — as a prediction policy problem.27 This means that the treatment effects of different policies and the targeting of these policies in time and space both need to be studied quantitatively. However, important limitations and potential pitfalls remain. Current conflict models have limited ability to make causal inferences and are sometimes informed by outdated data-gathering.

Even more serious is the possibility that predictive models can be self-fulfilling or self-defeating. For example, a prediction of war could cause local populations to flee, raising tensions that themselves trigger conflict. Also, care is needed in defining peace and ensuring that “peaceful” outcomes make a difference to the lives of real people such as refugees and those who have experienced trauma. Understanding these kinds of questions requires granular data gathered on a vast scale to inform decision-making and the cost-effective use of resources.

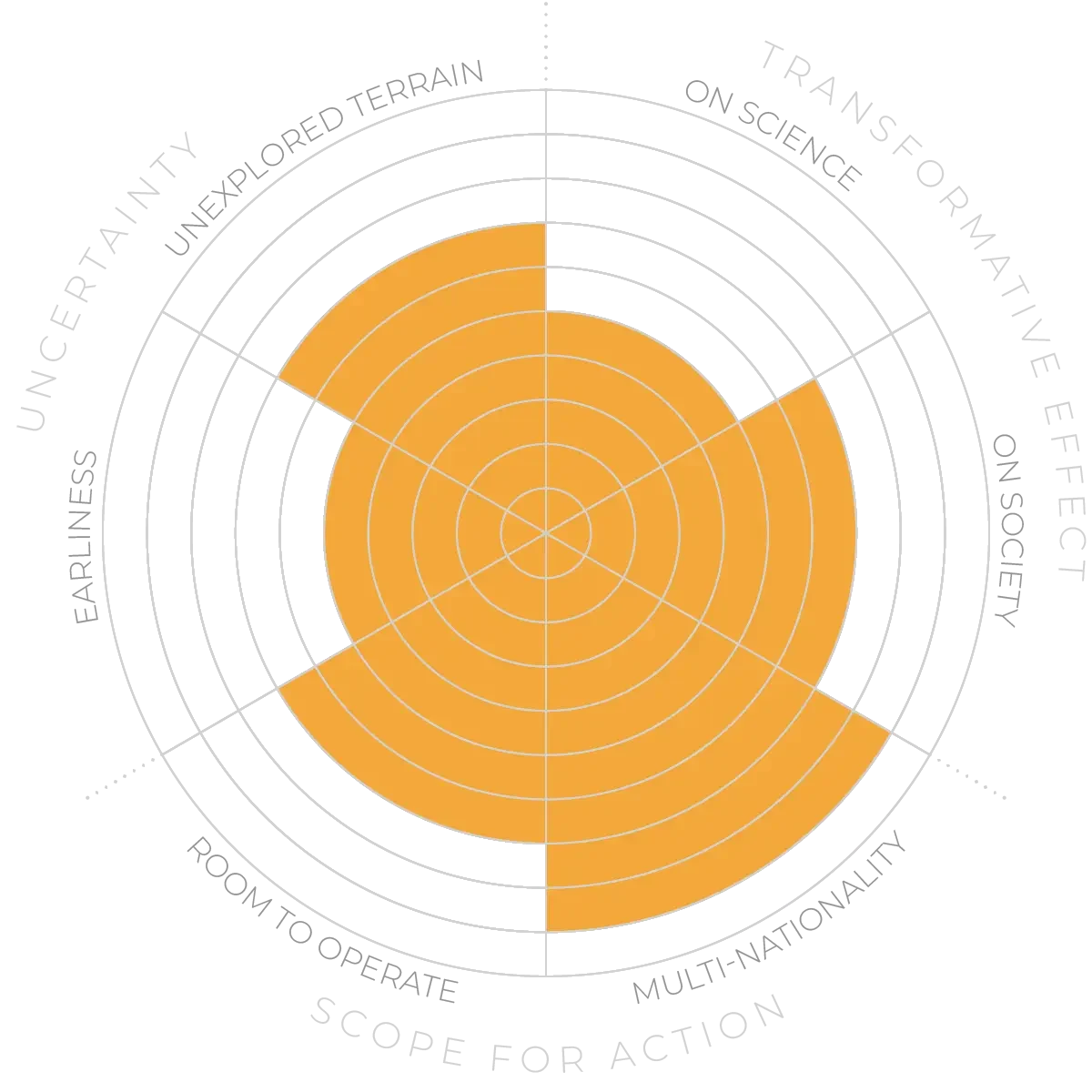

Predictive peacebuilding - Anticipation Scores